What are the Implications of the Overturning of Roe v. Wade for Racial Disparities?

Introduction

Women of color have much at stake in the June 2022 Supreme Court ruling in the case Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. The decision overturned the longstanding Constitutional right to abortion and eliminated federal standards on abortion access that had been established by earlier decisions in the cases, Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Going forward, it will be up to each state to establish laws protecting or restricting abortion in the absence of a federal standard.

State laws range from complete abortion bans with criminal penalties to abortion protections that include funding for clinics, and legal protections for clinicians. In some states, abortion provision will remain legal and available because the states have had policies in place prior to the Dobbs decision that protect access even in the absence of Roe. Another group of states do not have any explicit laws either upholding abortion rights or prohibiting abortion, and access to services is mixed in these states. Finally, since the Supreme Court ruling, several states have already outlawed provision of abortion services, and more states are expected to act in the coming weeks. These 17 states had policies in place prior to the decision that would effectively outlaw abortions soon after a ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade. Many of these states are in the South, which has large shares of Black and Hispanic women, the Plains which has a large Indigenous population, and the Midwest. To obtain an abortion, women in states that prohibit abortions would likely have to travel out of state, which will result in disproportionate barriers to accessing abortions for people of color.

In this brief, we present data on abortions by race/ethnicity and show how overturning Roe v. Wade disproportionately impacts women of color, as they are more likely to obtain abortions, have more limited access to health care, and face underlying inequities that would make it more difficult to travel out of state for an abortion compared to their White counterparts. Throughout this brief we refer to “women” but recognize that other individuals also have abortions, including some transgender men, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming persons. This brief is based on KFF analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), American Community Survey (ACS), Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS), and Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) (see Methods).

How do Abortions Vary by Race/Ethnicity?

Data on abortion by race and ethnicity are limited. The federal Abortion Surveillance System from the CDC provides national and state-level statistics on abortion annually, based on data that is reported by states, DC, and New York City. State reporting is voluntary, and while most states do participate, one notable exception is California, which has many protections for abortion access and is one of the most racially diverse states in the nation. Furthermore, availability of data on race and ethnicity varies among states. The most recent data in the Surveillance System, from 2019, only includes racial/ethnic data from 29 states and DC and is generally only available for White, Black, and Hispanic women. While we present the data from the Surveillance system in this brief, we recognize these limitations.

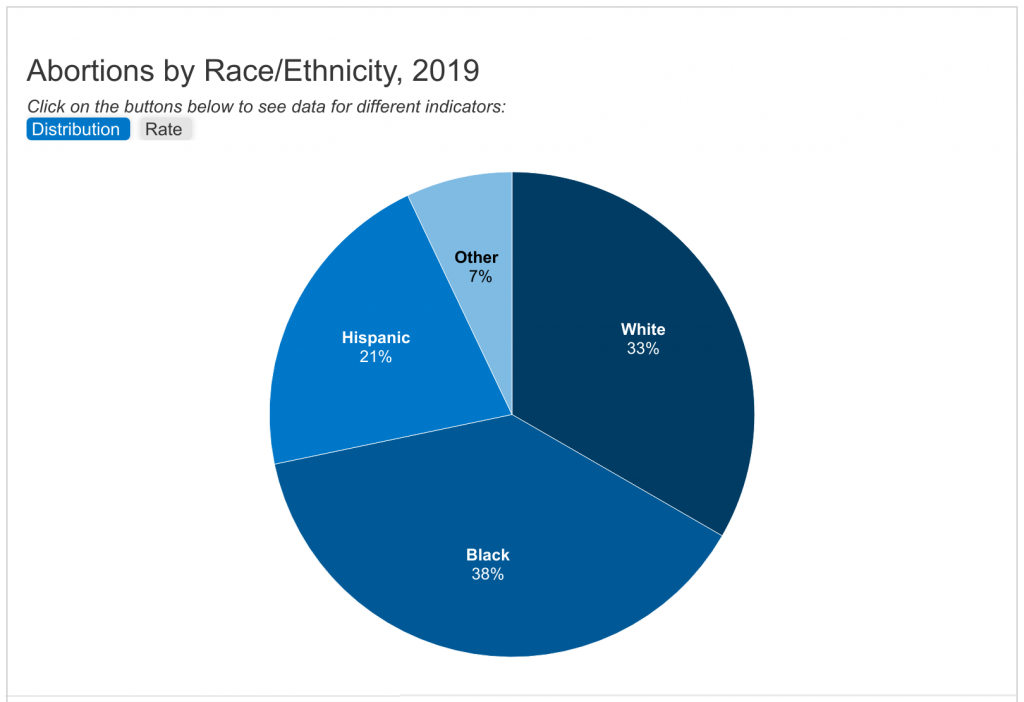

More than half of abortions are among women of color based on available data. In 2019, almost four in ten of abortions were among Black women (38%), one-third were among White women (33%), one in five among Hispanic women (21%), and 7% among women of other racial and ethnic groups (Figure 1). The abortion rate was highest among Black women (23.8 per 1,000 women), compared to 11.7 among Hispanic women, and 6.6 among White women (Figure 1). Data for other racial/ethnic groups were not available.

The vast majority of abortions across racial and ethnic groups are in the first trimester. Approximately eight in ten abortions among White (81%) and Hispanic women (82%) and three-quarters of abortions among Black women (76%) occur by nine weeks of pregnancy (Figure 2). Across all racial and ethnic groups, just over one in ten abortions occur between 10 and 13 weeks of gestation, and less than 10% occur in the second trimester. Prior to the Dobbs decision, the federal standard allowed the provision of abortions to the point of fetal viability (generally considered about 24 weeks of gestation), although many states had enacted legislation setting gestational limits before this point. While many of the pre-viability gestational limits were not in effect prior to the Dobbs ruling, in the absence of the federal standard now, states can bar abortions altogether and implement gestational limits prior to viability.

There are a variety of potential reasons why abortion rates are higher among some women of color. As shown below, overall, Black, Hispanic, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) women have more limited access to health care, which affects women’s access to contraception and other sexual health services that are important for pregnancy planning. Data show that, overall, current contraception use is higher among White women (69%) compared to Black (61%) and Hispanic (61%) women. Some women of color live in areas with more limited access to comprehensive contraceptive options. In addition, the health care system has a long history of racist practices targeting the sexual and reproductive health of people of color, including forced sterilization, medical experimentation, the systematic reduction of midwifery, just to name a few. Many women of color also report discrimination by individual providers, with reports of dismissive treatment, assumption of stereotypes, and inattention to conditions that take a disproportionate toll on women of color, such as fibroids. These factors have contributed to medical mistrust, which some women cite as a reason that they may not access contraception. In addition, inequities across broader social and economic factors — such as income, housing, and safety and education — that drive health, often referred to as social determinants of health, also affect decisions related to family planning and reproductive health.

Large majorities of women across racial and ethnic groups did not want the Supreme Court to overturn the Roe v. Wade decision and oppose criminalizing clinicians who provide abortion services. A May 2022 KFF survey found that across racial and ethnic groups, most women ages 18-49 said they did not want Roe v. Wade overturned and they think getting an abortion should be a personal choice (Figure 3). Majorities of women across groups also said that they opposed laws making it a crime for doctors to perform abortions and opposed laws allowing private citizens to sue people who provide or assist people with getting an abortion.

What are Potential Racial Disparities in Access to Abortions now that Roe v. Wade has been Overturned?

Over four in ten (43%) of women between ages 18-49 living in states where abortion has become or will likely become illegal are women of color. As of May 2022, 17 states had laws in place intended to immediately ban abortion, including four that had a law banning abortion in place predating Roe v. Wade. Overall, 18.1 million or 28% of women ages 18-49 live in these 17 states. Among women ages 18-49 living in these states, 22% are Hispanic,14% are Black, and 4% are Asian (Figure 4). (See Appendix Table 1 for the racial/ethnic distribution of women ages 18-49 by state.) Overall, nearly half (49%) of all AIAN women ages 18-49 live in these states, as do nearly three in ten White (29%), Hispanic (28%), and Black (28%) women in this age group, while less than one in five NHOPI (19%) and Asian (15%) women live in these states.

Variation in the availability of abortions by state due to the overturning of Roe v. Wade will likely result in women of color facing disproportionate barriers to accessing abortions. Women of color face more barriers to accessing health care in general and have more limited access to coverage of abortions. Moreover, due to underlying structural inequities, women of color have more limited financial resources and may face other increased barriers to accessing abortions if they need to travel out of state for one.

Health Coverage and Access Barriers

Women of color between ages 18-49 face greater barriers to accessing health care overall compared to their White counterparts. Among women in this age group, roughly a quarter of Hispanic (24%) and AIAN (24%) women are uninsured as are 16% of NHOPI women and 13% of Black women. In contrast, less than one in ten (9%) of White women lack insurance (Figure 5). (See Appendix Table 2 for state-level uninsured data by race/ethnicity.) Moreover, prior to the Dobbs decision, even among those who were insured, women of color had more limited access to abortion coverage since they are more likely to be covered by Medicaid, which has limited coverage for abortions. For decades, the Hyde Amendment has prohibited the use of federal funds for coverage of abortion under Medicaid, except in cases of rape, incest, or life endangerment for the pregnant person. States can choose to use state funds to pay for abortions under Medicaid in other instances. Currently, 16 states have a policy directing the use of their own funds to pay for abortions for low-income women covered by Medicaid beyond the Hyde limitations. Moreover, women of color are less likely to benefit from employer actions to cover travel costs for out-of-state abortions, since Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHOPI women ages 18-49 have lower rates of employer-sponsored insurance than their White counterparts. Beyond differences in insurance coverage, women of color are also less likely to have a personal doctor. Over four in ten (42%) Hispanic women and over a third of AIAN (35%) and NHOPI (34%) women between ages 18-49 do not have a personal doctor, compared to 22% of their White counterparts (Figure 5).

Social and Economic Access Barriers

Women of color have more limited financial resources and transportation options than White women, which would make it more difficult for them to travel out of state for an abortion. The median self-pay cost of obtaining an abortion exceeds $500. Traveling out of state will raise the cost of abortion due to added costs for transportation, accommodations, and childcare. Moreover, it may result in more missed work, meaning greater loss of pay. Data suggest that women of color would have more difficulty than White women affording these increased costs and may face other barriers that could prevent them from traveling to obtain an abortion and instead turning to self-managed abortions or continuing the pregnancies.

- Women of color are more likely to be low income (household income below 200% of the federal poverty level or $42,660 for a family of three as of 2019). AIAN (47%), Black (44%), and Hispanic (42%) women ages 18-49 are nearly twice as likely to be low income as White women (25%) (Figure 6). (See Appendix Table 2 for state-level data on the share of women who are low-income by race/ethnicity.)

- Women of color are less likely to have savings readily available to cover the costs of an abortion. For example, over half of Black women (53%) and nearly half of Hispanic women (47%) ages 18 and older would not cover a $400 emergency expense using cash or its equivalent compared to 27% of White women in this age group (Figure 6). These women reported they would pay using another method, such as with a credit card or by borrowing money, or that they would not have been able to cover the expense.

- Vehicle access is also more limited among women of color. Black women ages 18-49 are over three times as likely as their White counterparts to live in a household without access to a vehicle (13% vs. 4%), and AIAN and Asian women in this age group are twice as likely as White women to lack vehicle access (8% and 8%, respectively, vs. 4%) (Figure 6). Hispanic women are also more likely than White women to lack vehicle access, although the difference is smaller (6% vs 4%).

Some women of color may also have immigration-related fears about traveling out of state for an abortion. Among women ages 18-49, over a third of Asian women (35%), over a quarter (27%) of Hispanic women, and one in five (20%) NHOPI women are noncitizens, who includes lawfully present and undocumented immigrants (Figure 7). Many citizen women may also live in mixed immigration status families, which may include noncitizen family members. Noncitizen women and those living in mixed immigration status families may fear that traveling out of state could put them or a family member at risk for negative impacts on their immigration status or detention or deportation, especially if states move to criminalize abortion.

Women of color likely face greater challenges to accessing and navigating information on how to obtain an abortion compared to White women. Among women ages 18-49, 16% of AIAN, and nearly one in ten Black (8%), NHOPI (8%) and Hispanic (7%) women lack internet access, compared to 3% of White women (Figure 8). Moreover, nearly three in ten Hispanic (28%) and Asian (27%) women in this age group speak English less than very well, as do one in ten NHOPI women (10%) compared to just 1% of White women (Figure 8).

What are the Potential Implications of Overturning Roe v. Wade for Racial Disparities in Health, Finances, and Criminal Penalties?

There are already stark racial disparities in maternal and infant health, which may widen if it becomes more difficult for people to access abortions. Moreover, restrictions on access to abortions has negative economic consequences and may put people of color at increased risk for criminalization.

Some groups of color are at higher risk of dying for pregnancy-related reasons or infancy compared to White people. Black and AIAN people are more likely to die while pregnant or within a year of the end of pregnancy compared to White people (40.8 and 29.7 per 100,000 births vs. 12.7 per 100,000 births) (Figure 9). One study estimated that a total abortion ban in the U.S. would increase the number of pregnancy-related deaths by 21% for all women and 33% among Black women. Moreover, Black and NHOPI infants were two times as likely to die as White infants (10.8 and 9.4 per 1,000 compared to 4.6 per 1,000). AIAN infants also had a higher mortality rate than White infants (8.2 vs. 4.6 per 1,000) (Figure 9).

People of color are more likely to experience certain birth risks and adverse birth outcomes compared to White people. Specifically, as of 2020, higher shares of births to Hispanic, Black, AIAN and NHOPI people were preterm, low birthweight, and among those who received late or no prenatal care compared to White people (Figure 10).

Births among Asian people were also more likely to be low birthweight than those to White people. Moreover, the birth rate among Black, Hispanic, AIAN, and NHOPI teens was over two times higher than the rate among White teens (Figure 11). Research has found that state-level abortion restrictions were associated with disproportionately higher rates of adverse birth outcomes, including preterm birth, for Black individuals, and that inequities widened as states became more restrictive.

Denying women access to abortion services has negative economic consequences. Many women who are not able to obtain abortions will have children that they hadn’t planned for and face the associated costs of raising a child. In addition to the direct costs, lack of abortion access can affect women’s longer-term educational and career opportunities. Research from the Turnaway Study, which examined the impact of state-level gestational limits on abortion, found a range of negative economic effects of abortion denials, including higher poverty rates, financial debt, and poorer credit scores among women who were not able to obtain abortions compared to women who received abortions. The study also found negative socioeconomic impacts for the children born to women who were denied abortions, which may exacerbate existing racial disparities in income. Poverty rates are already much higher among children of color than White children, and research shows poor children experience negative long-term outcomes, including lower earnings and income, increased use of public assistance, greater likelihood of committing crimes, and more health problems.

People of color may be at increased risk for criminalization in the post-Roe environment. A long history of racism and judicial policy in this country has led to disproportionately higher rates of criminalization among people of color, which has also affected reproductive health care and is likely to grow as abortion care is criminalized. While most state-level abortion bans criminalize clinicians for providing abortion care, some states, such as Texas, Oklahoma, have enacted laws that allow individuals to sue anyone who aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion, for civil penalties starting at $10,000. Increased fear of criminalization of abortion may also result in more limited access to services to manage miscarriages or stillbirths since almost all of the health care services used in these cases are identical to those used in abortions. Some clinicians may hesitate to provide these services because of concerns they could be conflated with providing an abortion, and some pregnant people may be reluctant to seek these services due to fear of criminalization. Prior to the Dobbs ruling, there were already cases of women criminalized for their own miscarriages, stillbirths, or infant death, and the women involved were overwhelmingly low-income and women of color.

Conclusion

Prior to the Dobbs decision, people of color already faced significant disparities in maternal and infant health. With Roe now overturned, people of color are likely to be disproportionately affected by state actions to fully prohibit or implement extensive restrictions on abortions as they are more likely to seek abortions and more likely to face structural barriers that will make it more difficult to travel out of state for an abortion, including more limited access to health care and fewer financial and transportation resources. Increased barriers to abortion for people of color may widen the already existing large disparities in maternal and infant health, have negative economic consequences for families, and increase risk of criminalization for people of color.

| This analysis uses data from multiple sources including the 2019 American Community Survey, the 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the 2021 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking, as well as from several online reports and databases including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) on abortion surveillance, National Vital Statistics Reports, the 2017 CDC Natality Public Use File, and the CDC WONDER online database. Unless otherwise noted, race/ethnicity was categorized by non-Hispanic White (White), non-Hispanic Black (Black), Hispanic, non-Hispanic American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), non-Hispanic Asian (Asian), and non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI).

Data on the share of women ages 18 and older who would not cover a $400 emergency expense completely using cash or its equivalent is from the 2021 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking and is defined as the share who would not have paid with cash, savings, or a credit card paid off at the next statement. These respondents said they would have paid the expense by using a credit card and then carrying a balance, borrowing from a friend or family member, using money from a bank loan or line of credit, using a payday loan, deposit advance, or overdraft, selling something, or said they would not have been able to cover the expense. However, some who would not have paid with cash or its equivalent likely still had access to $400 in cash. Instead of using that cash to pay for the expense, they may have chosen to preserve their cash as a buffer for other expenses. |

Appendix