The BA.5 Wave Is What COVID Normal Looks Like

After two-plus years of erupting into distinguishable peaks, the American coronavirus-case curve has a new topography: a long, never-ending plateau. Waves are now so frequent that they’re colliding and uplifting like tectonic plates, the valleys between them filling with virological rubble.

With cases quite high and still drastically undercounted, and hospitalizations lilting up, this lofty mesa is a disconcerting place to be. The subvariants keep coming. Immunity is solid against severe disease, but porous to infection and the resulting chaos. Some people are getting the virus for the first time, others for the second, third, or more, occasionally just weeks apart. And we could remain at this elevation for some time.

Coronavirus test-positivity trends, for instance, look quite bad. A rate below 5 percent might have once indicated a not-too-bad level of infection, but “I wake up every morning and look … and it’s 20 percent again,” says Pavitra Roychoudhury, a viral genomicist at the University of Washington who’s tracking SARS-CoV-2 cases in her community. “The last time we were below 10 percent was the first week of April.” It’s not clear, Roychoudhury told me, when the next downturn might be.

Part of this relentless churn is about the speed of the virus. SARS-CoV-2, repped by the Omicron clan, is now spewing out globe-sweeping subvariants at a blistering clip. In the United States, the fall of BA.2 and BA.2.12.1 have overlapped so tightly with the rise of BA.5 that the peaks of their surges have blended into one. And a new, ominous cousin, BA.2.75, is currently popping in several parts of the world.

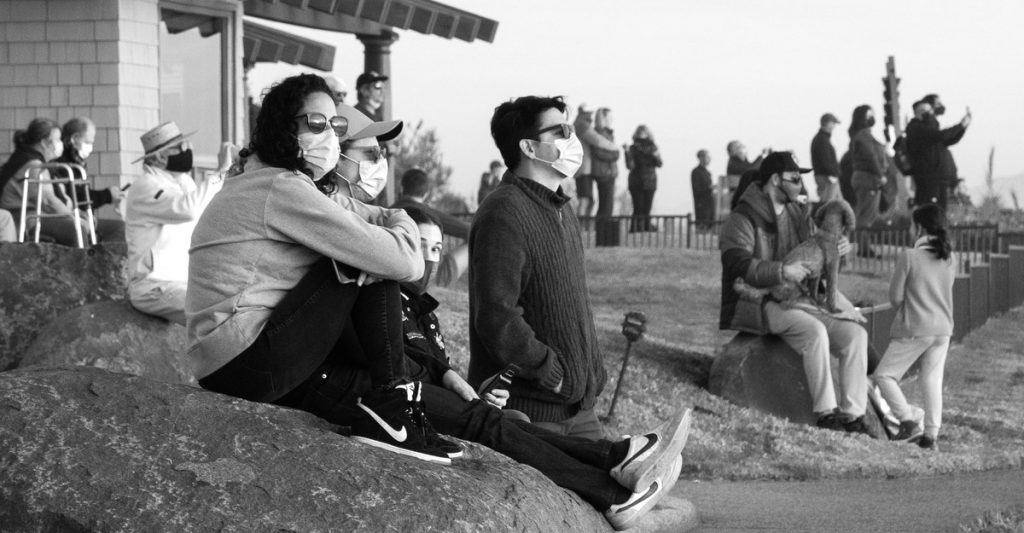

At the same time, our countermoves are sluggish at best. Pathogens don’t spread or transform without first inhabiting hosts. But with masks, distancing, travel restrictions, and other protective measures almost entirely vanished, “we’ve given the virus every opportunity to keep doing this,” says David Martinez, a viral immunologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

More variants mean more infections; more infections mean more variants. It’s true that, compared with earlier in the pandemic, hospitalization and death rates remain relatively low. But a high rate of infections is keeping us in the vicious viral-evolution cycle. “The main thing is really this unchecked transmission,” says Helen Chu, an epidemiologist and vaccine expert at the University of Washington. We might be ready to get back to normal and forget the virus exists. But without doing something about infection, we can’t slow the COVID treadmill we’ve found ourselves on.

The speed at which a virus shape-shifts hinges on two main factors: the microbe’s inherent capacity for change, and the frequency with which it interacts with hospitable hosts.

Coronaviruses don’t tend to mutate terribly quickly, compared with other RNA viruses. And for the first year or so of the pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 stuck to that stereotype, picking up roughly two mutations a month. But then came Alpha, Delta, Omicron and its many subvariants—and SARS-CoV-2 began to outstrip the abilities of even flu viruses to birth versions of itself that vaccinated and previously infected bodies can’t easily recognize. BA.1 sported dozens of typos in its genome; BA.2 was able to rise quickly after, in part because it carried its own set of changes, sufficient to stump even some of the defenses its predecessor had raised. The story was similar with BA.2.12.1—and then again with BA.4 and BA.5, the wonkiest-looking versions of the virus that have risen to prominence to date.

Nothing yet suggests that SARS-CoV-2 has juiced up its ability to mutate. But subvariants are slamming us faster because, from the virus’s perspective, “there’s more immune pressure now,” says Katia Koelle, an evolutionary virologist at Emory University. Early on in the pandemic, the virus’s primary need was speed: To find success, a variant “just had to get to somebody first,” says Verity Hill, a viral genomicist at Yale. Alpha was such a revision, quicker than the OG at invading our airways, better at latching onto cells. Delta was more fleet-footed still. But a virus can only up its transmissibility so much, says Emma Hodcroft, a viral phylogeneticist at the University of Bern. To keep infecting people beyond that, SARS-CoV-2 needed to get stealthier.

With most of the world now at least partially protected against the virus, thanks to a slew of infections and shots, immune evasion is “the only way a new variant can really spread,” Hill told me. And because even well-defended bodies have not been able to fully prevent infection and transmission, SARS-CoV-2 has had ample opportunity to invade and find genetic combinations that help it slither around their safeguards.

That same modus operandi sustains flu viruses, norovirus, and other coronaviruses, which repeatedly reinfect individuals, Koelle told me. It has also defined the Omicron oligarchy. And “the longer the Omicron dominance continues,” Hill told me, the more difficult it will be for another variant to usurp its throne. It’s unclear why this particular variant has managed a monopoly. It may have to do with the bendability of the Omicron morphs, which seem particularly adept at sidestepping antibodies without compromising their ability to force their way inside our cells. Scientists also suspect that at least one Omicron reservoir—a highly infected community, a chronically infected individual, or a coronavirus-vulnerable animal—may be repeatedly slingshotting out new subvariants, fueling a rush of tsunami-caliber waves.

Whatever its secret, Team Omicron has clearly spread far and wide. Trevor Bedford, who studies viral evolution at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, estimates that roughly 50 percent of the U.S. may have been infected by early members of the BA gang in the span of just a few months; each encounter has offered the virus countless opportunities to mutate further. And if there’s a limit to the virus’s ability to rejigger its genome and elude our antibodies again, “we haven’t detected it yet,” Martinez, of UNC Chapel Hill, told me. Such malleability has precedent: Versions of the H3N2 flu virus that have been bopping around since the ’60s are still finding new ways to reinvade us. With SARS-CoV-2, the virus-immunity arms race could also go on “very, very long,” Koelle told me. To circumvent immunity, she said, “a virus only has to be different than it was previously.”

So more variants will arise. That much is inevitable. The rate at which they appear is not.

Three things, Koelle told me, could slow SARS-CoV-2’s roll. First, the virus’s genome could get “a little more brittle, and less accepting of mutations,” she said. Maybe, for instance, the microbe’s ability to switch up its surface will hit some sort of ceiling. But Koelle thinks it’s unwise to count on that.

Instead, we, the virus’s hosts, could give it fewer places to reproduce, by bolstering immunity and curbing infections. On the immunity front, the world’s nowhere yet near saturated; infections will continue, and make the average person on Earth a crummier place to land. Better yet, vaccinations will shore up our defenses. Billions of people have now received at least one dose of a COVID-19 shot—but there are still large pockets of individuals, especially in low-income countries, who have no shots at all. Even among the vaccinated, far too few people have had the three, four, or even five injections necessary to stave off the worst damage of Omicron and its offshoots. Simply getting people up to date would increase protection, as could variant-specific updates to vaccine recipes, likely due soon in the U.S. and European Union.

But the appetite for additional shots has definitely ebbed, especially in the U.S. Retooled recipes also won’t see equitable distribution around the globe. They may even end up as a stopgap, offering only temporary protection until the virus gets “pushed to a new point” on its evolutionary map and circumvents us again, Hill said.

Which leaves us with coordinated behavioral change—a strategy that exactly no one feels optimistic about. Precautionary policies are gone; several governments are focused on counting hospitalizations and deaths, allowing infections to skyrocket as long as the health-care system stays intact. “Everyone just wants some sense of normalcy,” UW’s Roychoudhury said. Even many people who consider themselves quite COVID-conscious have picked up old social habits again. “The floodgates just opened this year,” Martinez said. He, too, has eased up a bit in recent months, wearing a mask less often at small gatherings with friends, and more often bowing to peer pressure to take the face covering off. Ajay Sethi, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, still works at home, and avoids eating with strangers indoors. He masks in crowded places, but at home, as contractors remodel his bathrooms, he has decided not to—a pivot from last year. His chances of suffering from the virus haven’t changed much; what has is “probably more my own fatigue,” he told me, “and my willingness to accept more risk than before.”

The global situation has, to be fair, immensely improved. Vaccines and treatments have slashed the proportion of people who are ending up seriously sick and dead, even when case rates climb. And the virus’s pummel should continue to soften, Hill told me, as global immunity grows. Chu, of the University of Washington, is also optimistic that SARS-CoV-2 will eventually, like flu and other coronaviruses, adhere to some seasonality, becoming a threat that can be managed with an annually updated shot.

But the degree to which the COVID situation improves, and when those ease-ups might unfold, are not guaranteed—and the current burden of infection remains unsustainably heavy. Long COVID still looms; “mild” sicknesses can still leave people bedridden for days, and take them away from school, family, and work. And with reinfections now occurring more frequently, individuals are each “more often rolling the die” that could make them chronically or seriously ill, Hodcroft, of the University of Bern, told me. In the Northern Hemisphere, that’s all happening against the backdrop of summer. The winter ahead will likely be even worse.

And with transmission rates this high, the next variant may arrive all the sooner—and could, by chance, end up more severe. “How much do we want to restrict our own freedoms in exchange for the injury that may be caused?” Hodcroft said. “That’s something that hard science can’t answer.”